Tips for hikers

My advice is “as soon as possible.” This is especially true for hikes that take place on the east side of the valley: in summer the sun beats down on you from early morning, and it is best to be as high as possible when it starts to beat down in earnest.

But it’s a good suggestion for any trail: very often summer days in Gressoney have clear skies until mid-day, when the first clouds begin to appear, which might even produce drizzle during the afternoon. This is even more true for hikes that take place very close to Mount Rosa, which fogs up faster than the rest of the valley.

This is why it is a good idea to take advantage of the morning window of good weather as much as possible, so that you arrive at your destination in the best possible visibility conditions-there is nothing worse than having toiled for hours to get to the top of the Alta Luce, and look out over Rosa to see nothing but clouds!

There is one last reason: people are normally lazy :-) and if you appreciate reaching the summit in solitude, it is much better to start when others are still in bed!

For longer hikes, this means leaving practically at dawn: once you manage to overcome the initial discomfort, you will soon realize that the advantages undeniably outweigh the disadvantages.

It happened several times that it started to rain during my walks, but I had never been under the thunder of a thunderstorm.

It happened to me a few days ago: the forecast said there would be a chance of rain in the late afternoon, but instead the thunderstorm started around 11:30 a.m. while I was on the summit of Rothore (above Zube Pass, reached via the path 4 from Stafal), and investigating in retrospect I found that I had protected myself in the wrong way.

The first drops began to fall as I unclimbed the summit cliffs, so I took shelter in a cave right between those cliffs. I waited sitting comfortably down there for it to stop (it also hailed, and not far away, at Zube Pass, so much of it fell that it looked like snow from a distance), and then I got back on the road, telling myself lucky for the excellent shelter I had found.

This page from the Aosta Valley Civil Defense states that what I have done is absolutely not recommended. I reproduce for convenience at the end of the text all the rules regarding how to behave in the mountains during thunderstorms.

Below I highlight two rules in particular, and the mistakes I made.

- Rule 6: Move quickly away from peaks and ridges; be careful of ropes and cables of via ferrata routes, especially when wet; do not stay under isolated rocks or trees; in forests stay away from the trunks of taller trees and low branches;

Instead, I stayed under the isolated rocks of the summit, so in the absolute least suitable place.

- Rule 12: lightning can be dangerous not only if it strikes us directly, but also because of the so-called “step current”: the lightning current remains on the ground surface and decreases in intensity as it moves away from the point of fall, consequently it is important to touch the ground at only one point, such as by hopping or crouching with feet together (the potential difference between the ground under one foot and the other can be dangerous); avoid lying down or leaning against the rock;

I was sitting and leaning with my whole back on the rock. With feet wide apart.

What I should have done is to try to get down as far as possible right away, and then crouch down somewhere in the open, keeping my feet together: getting wet as a chick, but staying away from isolated boulders.

- Rule 1: Always inquire at guide offices about route conditions and weather forecasts, if you have not already done so from home;

- Rule 2: If you notice vertically developing clouds already in the morning, then thunderstorms are likely to develop later in the day; the higher the haze and mugginess in the valleys, the further this probability increases;

- Rule 3: To predict the movement of thunderstorms already in place, observe in which direction the highest part of the cumulonimbus (anvil) points;

- Rule 4: at night, the glow of lightning can be seen tens of kilometers away, while if we hear thunder, the thunderstorm is only a few kilometers away from us: a delay of about 10 seconds between lightning and thunder means that we are about 3 kilometers away from the thunderstorm;

- Rule 5: Remember that the average lifespan of a thunderstorm is about 1 h, and that the most intense phase hardly exceeds half an hour: consequently, seek shelter at the first signs of a thunderstorm (e.g., inside the caves, not at the mouth) and wait for the phenomena to subside;

- Rule 6: In all cases, move quickly away from peaks and ridges; be careful of ropes and cables of via ferrata routes, especially when wet; do not stay under isolated rocks or trees; in forests stay away from the trunks of taller trees and low branches;

- Rule 7: Avoid gullies, culverts and rocky chimneys: following moisture and drafts, lightning will creep into these openings;

- Rule 8: Do not shake hands with fellow hikers and stay about 10 meters apart;

- Rule 9: Do not stay in the vicinity of streams-they swell quickly and can become dangerous, especially for those who are “canyoning” or fishing;

- Rule 10: Do not light fires: heat has a strong catalytic function;

- Rule 11: Isolate yourself as much as possible from the terrain with whatever insulating material you have available: backpack, sleeping bag, rope (if dry); get rid of any metal objects (ice axes, crampons, skis, carabiners, pitons) by placing them some distance away;

- Rule 12: lightning can be dangerous not only if it strikes us directly, but also because of the so-called “step current”: the lightning current remains on the ground surface and decreases in intensity as it moves away from the point of fall, consequently it is important to touch the ground at only one point, such as by hopping or crouching with feet together (the potential difference between the ground under one foot and the other can be dangerous); avoid lying down or leaning against the rock;

- Rule 13: The current developed by even a very small bolt of lightning can be sufficient to cause respiratory or cardiac arrest, skin burns, and involuntary muscle contractions that can induce sudden uncontrolled movements or even cause bone fractures. Lightning strikes of high power generally result in death. People struck by lightning are not electrically charged and therefore there is no risk in giving them aid. Eighty percent of electrocution victims survive: mouth-to-mouth respiration and CPR can save lives!

The issue is simple: it is important to have at least a map on paper, which comes in very handy when planning the hike. The map for sale at the Pro Loco of Gressoney, scale 1:25,000, is excellent and absolutely sufficient, otherwise the second famous map of these areas is the one from L’Escursionista editore, “08 – Monte Rosa, Ayas, Gressoney, Alagna trail map,” also in the same scale.

But during the hike, in my opinion, it is essential to have a good electronic map with you on a cell phone. Not so much for normal walking as for times when you are in trouble: losing the path is entirely possible, and indeed happens quite frequently: when you lose it, finding it again may not be so trivial.

You might think, “just climb vertically until you cross it again,” but you can’t always do that: when you are moving sideways down a slope, if you are groping your way up too high or down too low, you may end up in dead-end (and perhaps dangerous) areas of the slope from which you will soon have to turn back, wasting time, energy, and motivation. With a map on a cell phone, it is immediate to see where you are in relation to where the trail should be, and so it is immediately clear in which direction we need to move to find the trail again.

My advice is to check the location on the electronic map as soon as you have any doubts about the trail you are on. In fact, it happens to slip without noticing into branches of the main path that are at first barely distinguishable, but after a few steps appear less clear, with more vegetation, with suspicious slopes… in that case, instead of holding on and continuing because “maybe it gets better later on,” it is much better to pull out your cell phone and do a safety check. In cases such as these, a paper map would be of little help, unless you have one that is extremely detailed and can “read the terrain” perfectly. In cases such as these, a paper map would be of little help, unless you have one that is extremely detailed and can “read the terrain” perfectly.

Which app to use?

There are so many map apps out there, both free and paid. The important thing is to use one that allows you to download maps offline, because obviously we are almost always walking in areas without cellular coverage, so it is essential that the map is already on our phone.

Please note: app maps normally contain the layout of the main trails, so it is not necessary to upload the GPX track of the trail you want to walk each time. You do this when you want to make sure you have an up-to-date trail, taking into account any changes to the route due to landslides or similar events.

I normally use a free app: maps.me. It is available for both IOS and Android, and allows you to download maps offline.

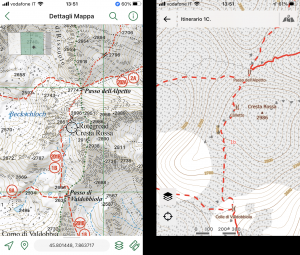

I also downloaded Avenza Maps, through which I was able to buy the map “Monte Rosa East – Gressoney Valley – Alagna Valsesia 1:25,000” (€7.99 in June 2022). It is the electronic version of the paper map published by The Hiking Editor (10€ in June 2022). The level of detail this electronic map offers is far superior to that of free apps, again based on opensource maps. Below is a striking example related to the Alpetto Pass area.

Having closed the map app chapter, there are two other apps that I now find indispensable.

One is PeakVisor. Also available as a free version for both IOS and Android, this app will return the name and altitude of all the peaks around us, near and far. When you arrive at a high point, it is good to look around and try to identify areas that you have yet to visit, to prepare yourself for what you will encounter: to do this, however, it is essential to understand what you are looking at. And the fastest way to do that, as an alternative to laboriously trying to associate what you see with the 2D map, is to use this app. Just frame a mountain, and PeakVisor will show its name. Simple and very useful. PeakVisor can also work offline: simply open it once in the area where you want to use it (when there is still network coverage) and the app will download to your phone the information it needs to identify all the surrounding mountains.

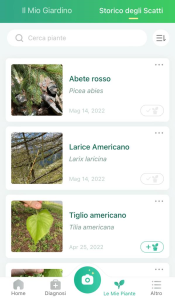

The second is PictureThis. Once we recognize the peaks with PeakVisor, we will also be able to name plants and flowers with this app, and what surrounds us will no longer have any secrets. For me, who can barely distinguish a red flower from a yellow leaf, it has the miraculous to see that this app can name a tree simply by photographing a leaf. Also free, the paid version offers additional services that I have not even explored, getting the name of the photographed plant is more than enough.

Important: Once we have chosen our apps, it is critical to “download the offline maps” in advance to prevent the phone from trying to download them the moment we open the app mid-path for the first time (almost certainly in the absence of data range).

It is also better to get a powerbank, or even better a powered case, that will allow enough charge for the whole day considering the heavy use you might make of the phone. It is advisable to turn off the wifi (and perhaps also the data connection) as soon as we leave, to reserve the phone’s charge for the only two basic functions: receiving the GPS signal, and showing the map and our location on the screen.

Foreword: The following is a description of my personal experience, without any pretense of wanting to suggest to anyone how one should behave.

I make it clear that I have chosen to bring what I need to cope with “possible and probable” weather conditions, and this is a completely personal decision and not an advisable one: those who are foresighted always prepare even for “possible but unlikely” weather conditions (for example: unseasonal snowfall).

A word, before moving on to the contents, about the backpack itself. I promised myself that I will never again in my life use a backpack without a mesh back, separate from the rest of the backpack. And I’m not talking about backpacks with “aerated” backs, which is nothing more than padding “with holes in it” that doesn’t make it aerated at all-I’m talking about backpacks whose backs consist of a lightweight plastic frame over which a mesh is stretched to keep the back separated from the load. This allows you to forget forever the horrible feeling of taking off your backpack and feeling your shirt completely stuck to your back from sweat. Tried it once, can never go without it again.

As for clothing, generally from June to mid-September I always wear a short-sleeved T-shirt and short pants. It may happen on very early morning starts that I wear a long-sleeved jersey as soon as I start, but the movement generally warms me up so much, so the jersey ends up in my backpack at the first turn.

I wear long pants if I plan to get to the glacier (obviously), or if the destination is above 3,000 meters where it is possible that, even on very sunny days, there will be freezing winds.

I then carry five additional items of clothing with me at all times, regardless of the season:

- the aforementioned long-sleeved shirt (made of fleece or other technical material, depending on the temperature I expect to encounter)

- a lightweight waterproof and windproof jacket

- a pair of lightweight fleece gloves (people often underestimate the importance of gloves, but when it’s cold, hands are the first things that start to suffer)

- a hat with a visor (useful both in sunny weather and, even more so since I wear glasses, in rainy weather)

- a woolen cap (very light, you forget you have it but when you need it it’s good to have).

The top pocket of the backpack also always contains a few small items (some may be useful in an emergency):

- A tiny bottle of protective sunscreen

- Cocoa butter

- A whistle (in an emergency, the best way to signal one’s presence from a distance)

- A thermal blanket (those with one silver layer and the other golden, useful for both protection from cold and heat depending on which side is used)

- A small set of patches

- A packet of mineral salt tablets

Besides water and provisions, of course, there are then other items that I put in my backpack depending on what the day might hold.

- Crossing a glacier (e.g., Gnifetti Hut): ice crampons, ice axe, helmet, winter gloves.

- Crossing a snowfield (e.g., Rissuolo Pass, Valfredda Pass): gaiters (in the middle of the summer season, when the snow is yielding), or crampons (at the edge of the summer season, when the snow can be very hard). Gaiters should not be underestimated: I crossed long sagging snowfields while wearing shorts, and the gaiters allowed me to do so without soaking my socks and keeping my feet perfectly dry.

- Progression facilitated by steel cables (e.g. Testa Grigia, Rifugio Quintino Sella): ferrata leather gloves (steel cables, if not in perfect condition, can cut like razors

- Progression along iron ladders or particularly exposed equipped routes (e.g. Mt. i Gemelli, Capanna Gnifetti): harness, via ferrata set, light helmet.

- Progressione su terreno prevalentemente roccioso dove potrebbe cadere qualche pietra dall’alto (ad es. Rifugio Mantova, Rifugio Quintino Sella, Testa Grigia): casco leggero.

Along with a pair of hiking poles, the satellite communicator mentioned here, thewatch (a Garmin Fenix 5X) and assorted photographic equipment, this is all I take with me for hiking.

I walk alone very often, and my cell phone very often stops getting a signal after less than an hour after leaving. This is especially a problem for those who stay at home, forced to endure a long silence with no chance to verify that everything is going well: those on the move, in fact, rationally or otherwise decided to take a chance, evidently deciding that the game was worth the candle. But those who stay at home, especially those who are apprehensive, are doomed to long days of anxiety, which is why, if you decide to go anyway, you have to be aware that there is a good deal of selfishness in this choice…

Yet there is a fairly inexpensive solution to this problem: it is not well known, which is why I am writing these notes (thanks for the umpteenth time to Bruno Borello for the tip): there are small satellite communicators that connect to the various satellite communication networks (with worldwide coverage) and allow you to automatically keep your location updated on a web page, exchange SMS or short emails with a predefined set of contacts, and call for help, in the unfortunate event that this is needed, by automatically sending your GPS location. If we then fail to even independently call for help, our contacts at home (seeing us, for example, standing in the same spot for hours on end, with no response) may decide to autonomously request the device for the last GPS location, and provide the information to the rescuers. As you can see, these are phenomenal features that would prevent many of the tragedies often reported in the newspapers.

To the cost of the device must be added the subscription to the satellite service, without which the device is practically useless: different levels can be chosen, differing mainly in the maximum monthly number of personalized messages that can be sent, or web-based location sharing.

There are several products: the most popular in Italy are those from Garmin and Spot: just Google“satellite messengers” to find them all.

I use a Garmin Inreach Mini. Currently (June 2022) it can be found online for just under €300 (version 2 recently came out, which costs €100 more). Small, very light but very durable, has a battery that lasts for days at a time.

Consumer subscription plans range from 15€ to 60€ for the “Annual” type (i.e., with a fixed monthly fee), and from 20€ to 75€ for the “Freedom” type: you only pay for the months when you are scheduled to use it (e.g., only the summer months), but there is an additional, fixed cost of 40€ per year. What varies from level to level is mainly the monthly number of “personalized” messages you want to be able to send and how often you want to share your location on the website: if you choose the minimum level, for example, each location share costs €0.10 (which is why I chose the next level, which allows unlimited location sharing).

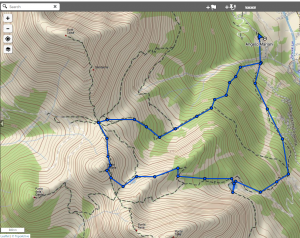

I am very pleased with it: I can send predefined calming messages (such as “I’ve made it to the top, everything’s fine,” or “I’m still climbing, everything’s fine”) without any limitations, my location is constantly updated every ten minutes on a website that I can have anyone I want to access (as seen in the image opposite), and of course in case of problems I can send an SOS to Garmin’s international rescue coordination center and communicate (again via text messages) with rescuers.

I have to say that it is a great added security that anyone who walks with some consistency in the mountains in places where cell phones don’t get reception should definitely have.

For years I carried the camera dangling over my shoulder, temporarily transferring it inside my backpack at delicate moments. A real torment: you always have to be careful where you place it to prevent it from hitting the rocks while swinging, on hot days the strap is extremely annoying, and in the long run the constant bouncing against your body becomes really irritating. Not to mention the fatigue: my full frame SLR, with 28-70 2.8 lens mounted, weighed 2Kg… in stops, the first thing I would do was to take the camera off my neck!

Switching to a mirrorless in 2020 was the first giant step forward, which I recommend to anyone who is still hesitant and which solved at least the significant weight problem at the root (my mirrorless with lens mounted weighs exactly one third compared to the SLR) but as long as I continued to carry it over my shoulder the other disadvantages were still very much in evidence. Things really changed as soon as I experimented with a shoulder mount.

I use a Peak Design model, but there are similar products from a thousand houses, and from more varied prices. These solutions consist of a clamp that attaches to the shoulder strap of the backpack at chest height, and a baseplate that screws into the machine’s threaded hole. The machine fits through the base plate into the stand, and stays nailed there in a position that practically allows you to forget about it.

This is the thing you cannot guess until you experience it: the machine attached to your chest in this way does not make itself felt in any way. Of course, it has to be a mirrorless: you can use this stand with SLRs as well, but 2Kg pressing on the chest definitely makes itself felt more.

Moreover, in this way you are able to grip the camera, when needed, much faster: how many times have I “missed the shot” because I wasted time untangling my arm from the shoulder strap, and the chamois was long gone…

Additional benefit: to protect the car from fleeting rain showers, so frequent in the mountains in summer, simply use…a plastic shower cap! Carried in this way, in fact, the car has no straps or shoulder straps between the boxes: as soon as the first drops fall, the bonnet (I use one of those given for free in hotels) is pulled out of the backpack and, unless it becomes a torrential downpour, the car will survive the experience without getting wet in the least.

As is well known, keeping hydrated during physical activity is essential. Also, rather than drinking a lot but a few times, it is much more effective for proper hydration to drink little but more often. But if every time you want to drink, you have to take your hands out of the paddle laces, take the backpack off your shoulders, take out the water bottle, open it, close it again, put it back in the backpack, put the backpack back on your shoulder… the urge to do it frequently escapes immediately.

The solution is the use of a“hydration bag,” also called a “camel back” or“water bag,” which allows you to quickly have as much water as you want, without having to take your backpack off your shoulders to drink.

I use a Decathlon model that costs just over 10 euros and has a capacity of 2 liters; there are, of course, an infinite number of them on the market, all equally reliable. Virtually every modern backpack has a dedicated pocket in which to house these pouches, and a hole in the side through which to pass the tube. The tube goes all the way to one of the shoulder straps, where you can attach it to one of the often-present loop loops, or you can simply leave it loose. The spout is always quick-closing, so there is no risk of it dripping on us while walking.

In this way you will have water available at all times, and you will be able to hydrate continuously and without the slightest disturbance. When you try it for the first time to use it, you will hardly go back: I regret that I tried it too late, because in all honesty I kind of snubbed it….

The closure of the bag is very effective, and the model I have been using for two years has never shown the slightest leakage-so you need not fear for the contents of your backpack. In addition, contrary to what I feared, the water contained does not take on any plastic taste. Perhaps the water warms up a little faster than when using a classic water bottle, but when you are very hot drinking “not cold” water is not that annoying.

For all these reasons, the use of a water bag instead of the classic water bottle is a simple but greatly enhancing expedient that increases the level of quality (and thus enjoyment) of our hikes.

Premise: I know this will sound like a carnival quack tirade trying to sell the miracle remedy, but the joy of having solved this problem is such that I love to share the solution in the hope that it will make many other hikers happy.

In fact, I suffered for a long time from blisters on my heel, both feet: I could only avoid them by using low boots. When I tackled hikes for which I was practically obliged to use high boots, in addition to preparing for the inevitable pain, I knew that I would then have to rest for a few days to give the blisters (which inevitably formed) a chance to heal.

I really tried everything: different models of boots, socks of various materials, under-socks of all kinds, various ointments to soften the foot before departure, preventive heel patches (regular and the very expensive Compeed), changing socks as soon as I began to feel discomfort while walking… nothing worked.

Until one day I happened upon a video, this one: Avoid blisters when hiking. The suggested that the blister-prone part be covered beforehand with this waxed tape, called Leukotape P. I decided to give it a try, discovered this tape on Amazon, ordered a roll… and from that day on, my feet have not suffered the damage of any blisters!

Using it is very simple: before setting off on the hike, simply apply a strip of tape about 8 centimeters long to the heel, trying not to form creases. The patch is so adhesive that it will not move for the duration of the hike, and you will find that it will remain attached even after showering if you forget to remove it first. Here on the left is a picture of my heel after applying the patch: as you can see, just a section is enough to cover the area on which the blister normally forms.

The patch, by thus remaining adherent to the skin, prevents the primary cause of blister formation, which is frictional heat induced by rubbing the skin against the sock. In case you find that it works, but still you have a small blister, the advice is to apply a second (perhaps smaller) layer of patch in order to further isolate the skin.

What is certain is that, since that day, I have been able to start wearing high boots without the slightest problem. If you want to be horrified, here is a picture of the aftermath of the last blister I got in my life, which was particularly bad because the blister had formed over a previous blister scar that had not yet healed 100%. As soon as I tried this patch, with the same boots and socks that had generated this obstruction, my problem was completely solved.

The tape is not so easy to find; it can be found on Amazon for about 20€ (the important thing is that it is the Leukotape P model, mind the P). It’s not cheap, but it’s actually worth as much gold as it weighs!

I buy a particular package, which also contains a white tape used, in combination with P tape, for the treatment of patella injuries. This combination, for unfathomable reasons, costs less on Amazon than the P… tape alone.